The Peoples Grocery was a grocery located just outside Memphis in a neighborhood called the "Curve". Opened in 1889, the Grocery was a cooperative venture run along corporate lines and owned by eleven prominent blacks, including postman Thomas Moss, a friend of Ida B. Wells. In March 1892 Thomas Moss and two of his workers, Will Stewart and Calvin McDowell, were lynched by a white mob while in police custody.

Leadup To The Lynching:

By the 1890's there were increasing racial tensions in the neighborhood and increasing tensions between the successful Moss and white grocer William Barrett, whose grocery, despite its bad reputation as a "low-dive gambling den" and a location where liquor could be illegally purchased, had had a virtual monopoly prior to Moss' venture.On Wednesday, March 2, 1892, the trouble began when a young black boy, Armour Harris, and a young white boy, Cornelius Hurst, got into a fight over a game of marbles outside the Peoples Grocery. When the white boy's father stepped in and began beating the black boy, two black workers from the grocery (Will Stewart and Calvin McDowell) came to his defense. More blacks and whites joined the fray, and at one point William Barrett was clubbed. He identified Will Stewart as his assailant.

On Thursday, March 3, Barrett returned to the Peoples Grocery with a police officer and were met by Calvin McDowell. McDowell told them no one matching Stewart's description was within the store. The frustrated Barrett hit McDowell with his revolver and knocked him down, dropping the gun in the process. McDowell picked it up and shot at Barrett, but missed. McDowell was subsequently arrested but released on bond on March 4. Warrants were also issued for Will Stewart and Armour Harris.

The warrants enraged the black residents of the neighborhood who called a meeting where they vowed to clean out the neighborhood's "damned white trash", which Barrett brought to the authorities' attention as evidence of a black conspiracy against whites.

On Saturday, March 5, Judge Julius DuBose, a former Confederate soldier, was quoted in the Appeal-Avalanche newspaper as vowing to form a posse to get rid of the "high-handed rowdies" in the Curve. That same day John Mosby, a black painter, was fatally shot after an altercation with a clerk in another white grocery in the Curve. As reported in the paper, Mosby cursed at the clerk after being denied credit for a purchase and the clerk responded by punching him. Mosby returned that evening and hit the clerk with a stick, whereupon the clerk shot him.

The Peoples Grocery men were increasingly concerned about an attack upon them, based on Dubose's threat and the Mosby shooting. They consulted a lawyer but were told since they were outside the city limits they could not depend on police protection and should prepare to defend themselves.

On the evening of March 5, six armed white men (including a county sheriff and recently deputized plainclothes civilians) headed toward the Peoples Grocery. The white papers claimed their purpose was to inquire after Will Stewart and arrest him if he was there. The account written by five black ministers in the St. Paul Appeal said the men arrived with a rout in mind for they had first gone to William Barrett's place then divided up and surreptitiously posted themselves at the front and back entrance to the Peoples Grocery. The men inside, already anticipating a mob attack, were being surrounded by armed whites and did not know they were officers of the law.

When the whites entered the store they were shot at and several were hit. McDowell was captured at the scene and identified as an assailant. The black postman Nat Trigg was seized by deputy Charley Cole but shot him in the face and managed to escape. The injured whites retreated to Barrett's store and more deputized whites were dispatched to the grocery where they eventually arrested thirteen blacks and seized a cache of weapons and ammunition.

Reports in the white papers described the shooting as a cold-blooded, calculated ambush by the blacks and, though none of the deputies had died, they predicted the wounds of Cole and Bob Harold, who was shot in the face and neck, would prove fatal. The St. Paul Appeal said as soon as the black men realized the intruders were law officers they dropped their weapons and submitted to arrest, confident they would be able to explain their case in court.

On Sunday, March 6, hundreds of white civilians were deputized and fanned out from the grocery to conduct a house-to-house search for blacks involved in "the conspiracy". They eventually arrested forty black people, including Armour Harris and his mother, Nat Trigg, and Tommie Moss. The story in the black paper contended that Moss was tending his books at the back of the store on the night of the shooting and couldn't have seen what happened when the whites arrived. When he heard gunshots he left the premises. In the eyes of many whites, however, Moss' position as a postman and the president of the co-op made him a ringleader of the conspiracy. He was also indicted in the white press for an insolent attitude when he was arrested.

Upon news of the arrest armed whites congregated around the fortress-like Shelby County Jail. Members of the black Tennessee Rifles militia also posted themselves outside the jail to keep watch and guard against a lynching.

On Monday, March 7, Tommie's pregnant wife Betty Moss came to jail with food for her husband but was turned away by Judge DuBose who told her to come back again in three days.

On Tuesday, March 8, lawyers for several of the black men filed writs of habeas corpus but DuBose quashed them. After news filtered out that the injured deputies were not going to die the tensions outside the jail seemed to abate and the Tennessee Rifles thought it was no longer necessary to guard the jail grounds, especially as the Shelby County Jail itself was thought to be impregnable. But, as Ida B. Wells would write in retrospect, the news that the deputies would survive was actually a catalyst for violence for the black men could not now be "legally" executed for their crime.

The Lynching:

On Wednesday, March 9, at about 2:30 a.m. seventy-five men in black masks surrounded the Shelby County Jail and nine entered. They dragged Tommie Moss, Will Stewart, and Calvin McDowell from their cells and brought them to a Chesapeake & Ohio railroad yard a mile outside of Memphis. What followed was described in such harrowing detail by the white papers that it was clear reporters had been called in advance to witness the lynching.At the railroad yard McDowell "struggled mightily" and at one point managed to grab a shotgun from one of his abductors. After the mob wrested it from him they shot at his hands and fingers "inch by inch" until they were shot to pieces. Replicating the wounds the white deputies had suffered they shot four holes into McDowell's face, each large enough for a fist to enter. His left eye was shot out and the "ball hung over his cheek in shreds." His jaw was torn out by buckshot. Where "his right eye had been there was a big hole which his brains oozed out." The Appeal-Avalanche added his injuries were in accord with his "vicious and unyielding nature."

Will Stewart was described as the most stoic of the three, "obdurate and unyielding to the last." He was also shot on the right side of the neck with a shotgun, and was shot with a pistol in the neck and left eye.

Moss was also shot in the neck. His dying words, reported in the papers, were, "Tell my people to go West, there is no justice for them here."

Aftermath:

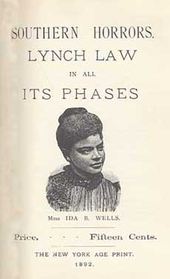

Cover of Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases

The lynching became a front page story in the New York Times on March 10 and countered the image of the "New South" that Memphis was trying to promote. The lynching sparked national outrage and Ida B. Wells' editorial embraced Moss' dying words and encouraged blacks to strike out for the West and "leave a town which will neither protect our lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts, but takes us out and murders us in cold blood when accused by white persons." This sparked an emigration movement that eventually saw 6,000 blacks leave Memphis for the Western Territories. At a meeting of one thousand people at Bethel A. M. E. Church in Chicago in response to this lynching as well as two earlier lynchings (Ed Coy in Texarkana, Arkansas and a woman in Raiville, Louisiana), a call by the presiding minister for the crowd to sing the then de facto national anthem, "America (My Country, 'Tis of Thee)" was refused in protest, and the song, "John Brown's Body" was substituted. The widespread violence and particularly the murder of her friends drove Wells to research and document lynchings and their causes. She began investigative journalism by looking at the charges given for the murders, which officially started her anti-lynching campaign.

Source: wikipedia.com